Undergraduate Research Intern Maps Coronary Heart Disease and Deprivation

In July 2024, CHICAS hosted an intern, Natasha Williams, funded through Lancaster University's undergraduate research internship programme. In this news item, she describes the work she has done as part of her internship.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a type of cardiovascular disease that occurs when the cardiac arteries are unable to deliver sufficient oxygen-rich blood to the heart, which typically occurs due to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques [1]. CHD is the second largest cause of death in the UK [2]. Deprivation, which can be defined as ‘a lack of adequate resources or of education, care, etc., leading to a low standard of living or reduced opportunities in life’ [3], has emerged as a CHD risk factor. However, an exact understanding of how and why the relationship between CHD and deprivation differs across England remains unknown. Better understanding this relationship could provide opportunities to develop interventions that could reduce CHD mortality rates in deprived areas, whilst also identifying areas that these interventions should be targeted towards.

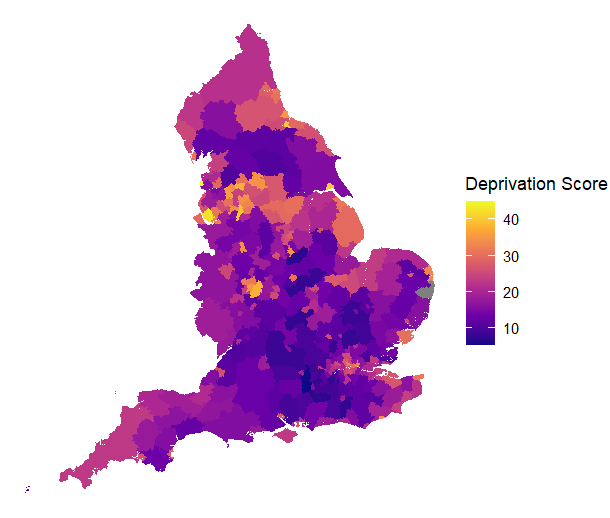

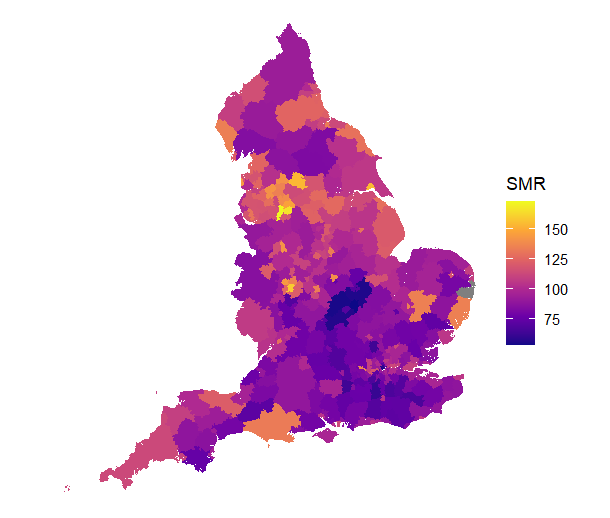

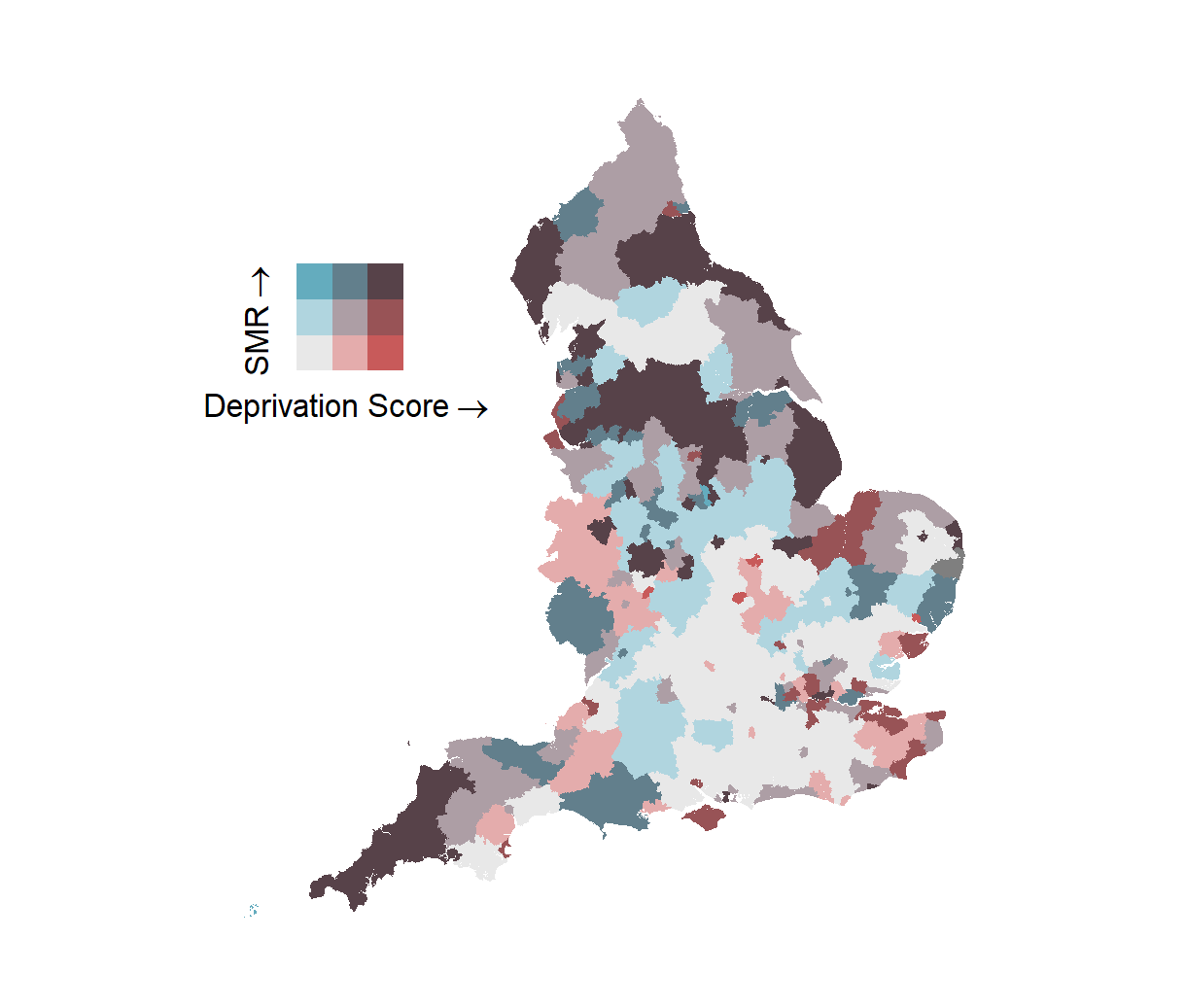

By combining publicly available datasets that included the age-standardised CHD mortality rates (SMR) [4] and deprivation scores (based on the English Index of Multiple Deprivation) for each area within England [5], a positive correlation between CHD mortality and deprivation was identified. This correlation was statistically significant, both in the overall population, and for males and females individually. These datasets were then further combined with publicly available geospatial data that defined the boundaries of each local authority area within England [6], to allow for visualisation of the relationship between SMR and deprivation across England.

It was found that the distribution of deprivation and CHD mortality rates were unequal across England, with high levels of deprivation and high CHD mortality rates congregating within pockets in the North East and North West (Figures 1 and 2, respectively). There was a statistically significant correlation between SMR and deprivation. The bivariate map (Figure 3) identified three regions, Northampton, Corby and Ipswich, which have lower than expected SMRs for their level of deprivation. This map also identified two regions, Broxtowe and the Isles of Scilly, which demonstrated high SMRs despite low levels of deprivation.

There were some differences in the relationship between SMR and deprivation between males and females, particularly in the North East. There were also sex-based differences in the regions that did not conform with the expected SMR/deprivation relationship, with females having six regions that had an abnormally high SMR despite low levels of deprivation, compared to two regions that displayed low deprivation and high SMR in males. However, the difference in this relationship for males and females was not statistically significant.

Further research is needed to fully understand why there is a link between deprivation and CHD mortality, although possible explanations include that people from deprived communities experience an increased prevalence of CHD risk factors [7,8] and a reduced access to healthcare [9,10]. This research supports the latter as Northampton and Ipswich, which both had a low SMR despite high deprivation, have a high availability of cardiac healthcare [11,12]. Research is also needed to develop interventions that interfere with this relationship, with the abnormal regions identified in this project providing possible locations for this research.

References

- NHLBI. Coronary Heart Disease - What Is Coronary Heart Disease? | NHLBI, NIH. Published December 20, 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/coronary-heart-disease

- British Heart Foundation. BHF statistics factsheet UK. Published online January 2024. www.bhf.org.uk/-/media/files/for-professionals/research/heart-statistics/bhf-cvd-statistics-uk-factsheet.pdf

- Oxford English Dictionary. deprivation, n. meanings, etymology and more | Oxford English Dictionary. Published 2023. Accessed July 4, 2024. www.oed.com/dictionary/deprivation_n

- NHS England. Mortality from coronary heart disease: indirectly standardised ratio (SMR), all ages, 3-year average, MFP. NHS England Digital. Published July 21, 2022. Accessed July 16, 2024. digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/compendium-mortality/current/mortality-from-coronary-heart-disease/mortality-from-coronary-heart-disease-indirectly-standardised-ratio-smr-all-ages-3-year-average-mfp

- ONS. Population profiles for local authorities in England - Office for National Statistics. Published April 1, 2020. Accessed July 16, 2024. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/populationprofilesforlocalauthoritiesinengland/2020-12-14

- ONS geography. Local Authority Districts (December 2009) Boundaries GB BFC. Published October 26, 2022. Accessed July 16, 2024. geoportal.statistics.gov.uk/datasets/dadb8baa3e414afeae0d6721458291b9/explore

- Birtwistle S, Deakin E, Wildman J, et al. The Scottish Health Survey. Published online December 5, 2023. www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-health-survey-2022-volume-1-main-report

- Ramsay SE, Morris RW, Whincup PH, et al. The influence of neighbourhood-level socioeconomic deprivation on cardiovascular disease mortality in older age: longitudinal multilevel analyses from a cohort of older British men. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(12):1224-1231. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-205542

- Schröder SL, Richter M, Schröder J, Frantz S, Fink A. Socioeconomic inequalities in access to treatment for coronary heart disease: A systematic review. International Journal of Cardiology. 2016;219:70-78. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.05.066

- Matetic A, Bharadwaj A, Mohamed MO, et al. Socioeconomic Status and Differences in the Management and Outcomes of 6.6 Million US Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2020;129:10-18.doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.05.025

- NHS. Northampton General hospital Cardiology Department. Accessed July 16, 2024. www.northamptongeneral.nhs.uk/Services/Our-Clinical-Services-and-Departments/Medicine/Cardiology/Cardiology.aspx

- Suffolk GP Federation. Cardiology – Suffolk GP Federation. Published 2024. Accessed July 16, 2024. suffolkfed.org.uk/healthcare-services/cardiology

Updated: Monday 29 July, 2024